When curator Chessy Ricca of Stuart’s Elliott Museum contacted Alchemy Fine Art Restorers to bring a portrait of Frances Langford (1913-2005) back to its full measure of beauty, it gave Kate Wood of Alchemy Fine Arts the opportunity to restore a painting that embodies multiple aspects of America’s entertainment heritage.

It also hit close to home. Although Langford entertained fans around the world, her heart was fond of Florida; and two decades after her death, she remains a beloved figure on the Treasure Coast.

Kate Wood carefully conserving other fine art paintings from the Elliott.

“It was an honor to help save this lovely painting. The tears and pressure dings were so deep that the canvas had to be removed from its stretcher bars and lined with a fresh canvas to stabilize it. After a deep clean and some major repairs, Frances Langford’s beauty and star power really emerged.”

Kate Wood, owner and lead restorer at Alchemy Fine Arts

The Purpose Behind the Painting

Examining the portrait, Kate recognized that it was designed as a magazine cover. Not only was there plenty of blank space around the main subject, but the artist also left pencil strokes along the canvas edge to mark the placement of design elements.

Cover illustration is a familiar field to patrons of the Elliott. The museum featured a comprehensive collection of similarly purposed works by Norman Rockwell and his mentor, J.C. Leyendecker in 2022-2023. That show helped foster an appreciation of the role magazine illustration played in the evolution of fine art technique. The above portrait of Frances Langford fits into that narrative, not only as an example of early airbrush work, but also as a precursor to the pop art portraiture of later artists.

However, because it was unsigned, the specific artist and publication behind this painting remained a mystery. To help solve it, Kate enlisted her husband — writer Greg Leatherman — to fill in the gaps. His research revealed interesting details about this portrait in relation to Frances Langford’s ascent to fame.

Discovering a Star

Born in Lakeland, Florida, Frances Langford’s career took off early in 1931 — when she was still just sixteen years old — after famed crooner Rudy Vallée heard her on a Tampa radio station. The affable megastar invited Langford to sing on his radio program at WNBC New York (chaperoned by her mother). Aside from a knack for introducing new talent to his massive audience, Vallée was also a keen advisor who guided Langford through early business decisions, such as turning down the first offer she received and holding out for better terms.

Langford’s captivating voice and physical beauty made her a crowd pleaser. Typically backed by radio orchestras, she performed on stations across America, and in December 1933, she hosted her own radio special on WNBC. It was the first of many.

Discovering an Artist

Frances Langford was featured on the cover of Radio Guide in June 1935. Founded by the Hearst publishing empire, the useful guide combined radio schedules with celebrity news. Today’s readers know this influential weekly by its modern name: TV Guide.

One of countless magazine covers Langford graced, it’s of interest here because it carries the signature of Charles E. Rubino (1896 – 1973). Rubino served as the art director for Hearst Publications in New York for many years and created covers for Radio Guide from at least 1935-1937.

The Italian-born Rubino was not only a talented illustrator, but he also helped change the way magazines looked by demonstrating that the airbrush was perfectly suited to magazine illustration. The artist’s considerable skill with this tool was undoubtably a deciding factor when Radio Guide switched from black and white cover photos to Rubino’s full-color portraits in February 1935. Across the next two years, Radio Guide would feature Langford for three of these covers. As Greg would soon discover, these covers were the keys that would unlock the mystery behind the restored portrait.

Silver Screen Inspiration Behind the Portrait

The painting featured in this post was inspired by one of Langford’s first big movie roles. As a publicity piece, it’s emblematic of how the Golden Age of Radio and the studio system of Hollywood intertwined during the Great Depression.

In the 1930s, performances on both the airwaves and the silver screen were turning singers like Bing Crosby, Dick Powell, Alice Faye, and Rudee Vallée into huge crossover stars. Like them, Langford’s radio success led to her own movie roles. This led to her being one of an elite group of performers awarded stars on the Hollywood Star Walk for both film and radio.

Having already appeared in a Broadway show and two short films, Langford burst into movie fame in August 1935. That’s when America first saw her perform her signature song, “I’m in the Mood for Love,” in Paramount’s Every Night at Eight. The melodic standard proved so popular that other artists rushed to record their own versions. Several of these charted in 1935, and it’s since been covered by countless performers — but in the hearts of movie lovers, the song will forever be associated with Ms. Langford.

MGM studios built on the publicity around Langford’s performance by casting the young starlet as herself in Broadway Melody of 1936, which was released just seven weeks later. The jazzy musical did well at the box office and was nominated for three Academy Awards. Once again, Frances Langford delivered a fabulous performance.

In light of this success, Radio Guide selected Langford to grace another cover of their publication. This time, the artist used her appearance in Broadway Melody of 1936 as a model. As seen below, it resulted in the painting now housed at the Elliott Museum.

The February 15, 1936, cover of Radio Guide. Frances Langford’s ruby red tuxedo and romantic songs made her the perfect choice for a magazine issued the week of Valentine’s Day.

Everybody Knew Her Name

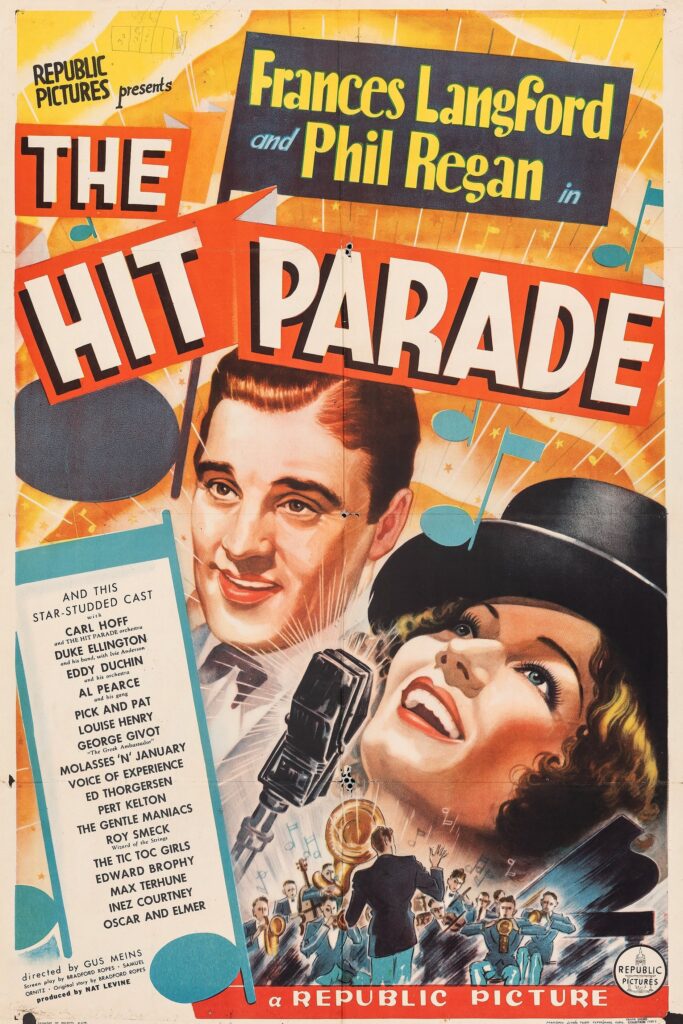

Every radio network and movie studio in America wanted Langford. By the time 1936 ended, she appeared in two more movies for Paramount and another for MGM. She did all this while starring on CBS radio’s Hollywood Hotel, which led to a 1937 supporting role in Warner Brothers’ film version, and a lead role in Republic’s The Hit Parade, which reprised her top hat look.

Even MGM’s Our Gang got in on the Langford craze when two of its child stars sang “I’m In the Mood for Love” in a short comedy that combined elements of Every Night at Eight and Broadway Melody of 1936.

Langford’s Lasting Impact

The portrait restored by Kate Wood was painted at a pivotal point in the career of Frances Langford. Working with the biggest stars of her time, she recorded numerous American standards, appeared in several classic musicals, and made millions laugh and cry. But she was far more than a celebrity.

During World War II, Langford struck an emotional chord with American G.I.’s while performing with Bob Hope’s U.S.O. Troop. She also wrote a Hearst newspapers syndicated column about her visits to wounded soldiers.

Langford’s smoldering voice, natural charm, and elegance fueled her career as a radio host, actor, and singer well-into the 1950s. She was also intelligent. In 1955, as rock and roll took over the radio waves, she went into semi-retirement in Florida where she enjoyed fishing and boating on the Indian River.

In Martin County, Langford is remembered as a generous philanthropist who founded the Outrigger Resort at Jensen Beach in 1961 (along with husband Ralph Evinrude). Thanks to Langford, the resort drew fans (and luminaries) from around the world. She performed there for decades.

See the Restored Portrait

As we communicated these discoveries about how Radio Guide‘s cover portrait of Langford fit into the arc of her early fame, curator Chessy Ricca of Stuart’s Elliott Museum shared some exciting news of her own.

The restored portrait featured in this post will be part of Elliott Museum exhibit celebrating the life of Frances Langford later in 2024. This welcome news comes as no surprise to those who’ve visited the museum’s Outrigger Café and Exhibit, which already features selected objects from her life. We’re curious to see what other forgotten treasures Ms. Ricca finds in the Elliott archives.

As regular patrons of this invaluable institution, the team at Alchemy Fine Art Restorers encourages you to visit this special exhibit and pay tribute to the “Florida Thrush,” aka the “Songbird of the Air,” aka the “Moonglow Girl,” and the “Sweetheart of the Fighting Fronts,” the unforgettable Frances Langford.