An illuminating interview with painter, teacher, and master art conservator Kate Wood.

Art conservator Kate Wood resurrects damaged paintings, sculptures, and porcelains from the dust-heap of history, but she doesn’t dwell in the past. Through her popular classes, she teaches aspiring artists to capture what they see in their mind’s eye. When she’s not doing either of these, she paints the world around her so realistically that her canvases are often mistaken for photographs. With this much passion for the Arts, it’s no wonder that so many people depend on her to teach, create, and restore beauty.

Growing in the Arts

Kate Wood comes from a military family, having lived in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, but she spent her teenage years in rural New England. She studied painting at the University of Massachusetts under the renowned James Hendricks and she also has a degree in Japanese Language and Linguistics.

“As a young adult” she says, “I was fascinated by tools. When it came to cars, I turned the wrench. When it came to furniture, I drove the nail. And when it came to art, I learned everything I could about technique, paint chemistry, even gilding frames.”

In 1991, she relocated to Stuart, FL to care for her ailing grandmother and loved the community so much, she stayed.

“I was determined to make a career in the arts,” says Kate. “but I only sold a half-dozen paintings a year, so I scrambled to make ends meet. I designed clothing; I owned a sign shop; I painted murals; I even worked as a set designer for a theater company operating out of The Lyric; but it wasn’t until I was hired as an art instructor at Georgia Abood’s Alizarin Crimson Art Studio that things really began to take off for me.”

In 2006, shortly after being hired as an art instructor, Kate began restoring art in the workshop of an art framer / restorer in Stuart, FL. The seven years during which she treated all manner of dirty and damaged art elevated her into a master of the craft. Now, as the go-to restorer for some of the top studios and galleries in South Florida, Kate is not just an accomplished painter and instructor, she’s one of a handful of world-class art conservators in Florida.

In Spring 2013, she incorporated Alchemy Fine Art Restorers, a licensed and insured studio offering the full-range of fine art services. Our interviewer sat down with Kate to find out just what it takes to rescue beautiful works of art.

How do you rescue art objects?

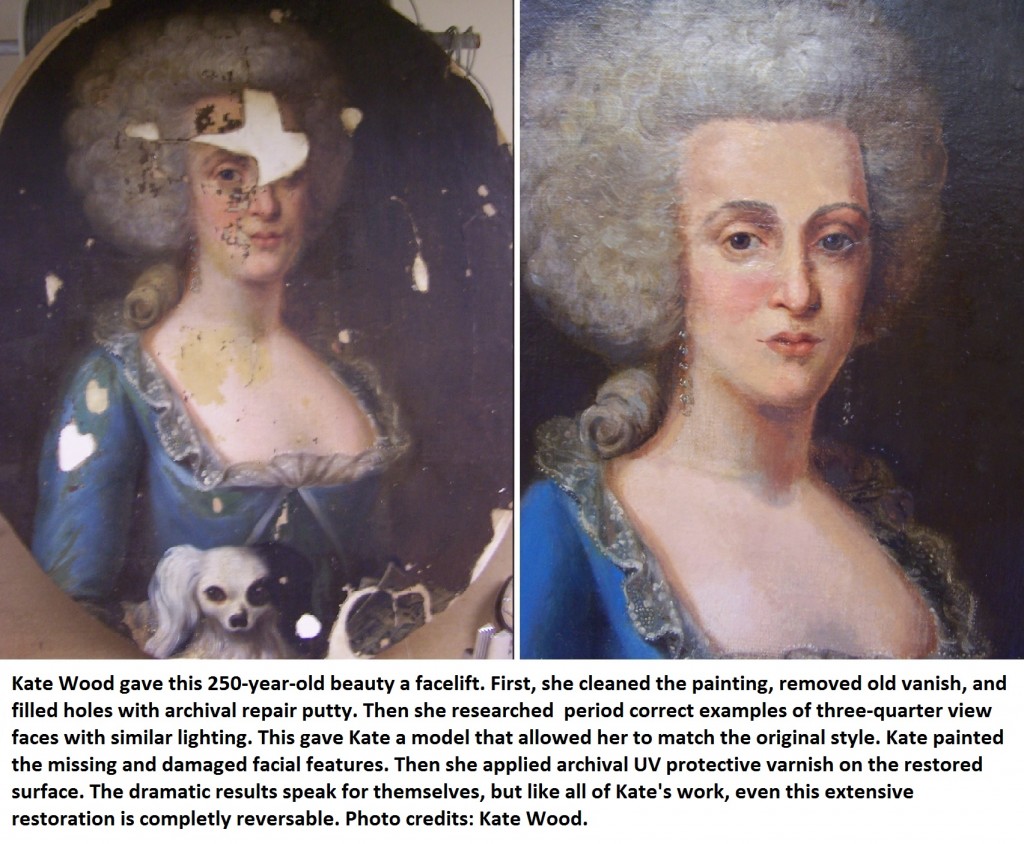

Kate Wood: Art gets dirty or damaged, just like floors and clothing. Oil paintings, for example, need to be cleaned about every 100 years. Sometimes the damage is extensive, including holes or rips, and other times it’s just a matter of removing old varnish, which takes off a century or more of dirt.

In other cases, a painting needs to be lined or in-painted, but no matter how much needs done, the restoration I do is always reversible. This not only honors the art, but it is a favor to future restorers. I can often tell the age of a painting by the last time it’s been restored, because people from different eras use different materials and techniques. One thing I’ve found in very old restorations is that they were lined with wheat paste backings that are easily removed, unless someone in the mean time put some Elmer’s glue in there. It happens more often than you may think. Elmer’s glue is a restorer’s nightmare. It’s difficult to remove and resists even the most advanced chemical procedures.

Wheat paste glue is organic and responsive to conservation efforts. Early wheat paste glue was basically flour and water and (other than bugs liking wheat just as much as we do), it doesn’t present as many problems for restorers. Of course, quite a few older paintings do have a certain amount of degradation from cockroaches. Sometimes I jokingly tell a customer “bug removal at no extra cost,” because bugs do come and eat at the old linings.

What do you see when you first look at a work of art?

Kate Wood: I can tell a lot about the time period by looking at what style of dress the subjects are wearing, or what skills the painter has. For an older oil painting, I look at the subject matter, but you can’t always go by that because some artists will paint from the past. I see the style of the frame. I see the age of the stretcher bars. So, you first look at the subject matter, then the frame, and then the back.

Is the frame gilded? Is it a good frame that was repainted in radiator paint? That sort of thing happens because well-meaning people thought they were helping dirty frames by repainting them. Of course it ruins the frame’s finish.

Now, turn it over. Look at the age of the wood of the stretcher bars. Is it original? How many marks are on the back? That shows how many times it has traded hands. Has the painting been relined? What kind of relining? If it’s wheat based, you’re looking at a painting that may be a couple of hundred years old, because that’s what they did then. Generally, an older painting that’s cared for and has been relined is loved. It’s hung away from direct light, and so forth, but it’s still going to get dirty and need cleaning. On the other hand, if a painting is very old hand and hasn’t been relined, you’re lucky if it’s still in good condition. Sometimes, it’s in tatters. But generally the older the painting, the more likely it’s been relined. These are the things I have to address every time I look at a painting.

Victorians were very funny about hiding signatures, but anytime there’s a discernible signature I try to safe it out. I never clean over a signature because artists in the past would often sign using varnish, because if you put a little varnish in your paint you can get a very smooth slick line, and get a nice tight signature, but if you were to clean that with varnish remover, it would ruin it. The other things, the things that aren’t evident at first, can be researched, either by looking up auction records, or doing a little detective work to find out who the artist was, or what the provenance of the painting is, perhaps discovering more as you clean a painting and more of the subject is revealed.

What inspires you as a restorer?

Kate Wood: When a new project comes in, often the piece is so dark and damaged that when it’s restored and brought out into the light, it takes your breath away. Unfortunately, a lot of people throw away damaged pieces they don’t realize can be saved, or they hide them away in the attic. Honestly, that’s part of what makes fine art valuable: and the result is a scarcity of older art. Even those objects that do survive remain endangered unless someone cares for them.

I’ve restored Rembrandts, Picassos, Courbets, and Corots that I felt incredibly privileged to touch, but it’s not always about monetary value. Sometimes you see an old wedding photo that’s destroyed, or a daguerreotype that’s stuck to the glass and pulled apart. Where does the value begin? Fine art gets more than its share of attention, while whole collections of cultural property may be ignored, but I don’t see it that way. I take just as much care restoring family portraits as I do a 16th century oil painting because, in both cases, I am rescuing something meaningful to the owner.

What was your first art restoration assignment?

Kate Wood: In 2006, a local restorer needed someone who could create a stencil to put on Victorian furniture, and he asked me. I had done lettering while working on theater sets and in making signs for my old business, so I came in and worked from some photos of the original stencils. The furniture was severely water damaged and the customer wanted the original Victorian stencil redone. I recreated them, redid all the stencils in oil paint over the finished furniture, and it was absolutely beautiful. It was just like it had been before the damage.

Two weeks later the restoration shop owner asked if I would work as an independent contractor. My skill set of painting, sculpting, and workshop skills were ideal for art restoration, but I never stopped learning. In 2013, after seven years serving as his lead restorer, the time came to strike out on my own and I incorporated Alchemy Fine Art Restorers.

The mission of Alchemy Fine Art Restorers has been to win business by doing the best possible work at the lowest possible cost. Of course, my overhead is much lower than a lot of places, because clients are working directly with the restorer. My pricing is straightforward, not a complicated formula, and I stand behind all the work I do by providing upfront estimates, detailed invoices, and doing whatever it takes to get the job right.

What should we be wary of when selecting a restorer?

Kate Wood: Everything the restorer does should be reversible. Restorers who came up in the 60s and 70s will sometimes use irreversible techniques, especially when treating work they don’t perceive as valuable. Well, this creates problems for both the integrity of the art, and for future restorers: forty years later, trying to undue Elmer’s glue on a Masonite board is a nightmare. It’s just unforgivable if you love art. I also disagree with some restorers’ attempts to age paintings, where they clean them and they find them too bright, and so they apply some horrible spray they get at a retail art supply store, and just make it look dirty. I find that reprehensible. This is not something that anyone who truly loves art would do.

One of the problems in art restoration today is people think that all classic art looks old. But, of course, the artist painted it as a new work. Deliberately antiquing a painting is misguided in my opinion. If you clean a piece of art and you see underneath that it is filled with light and brilliantly colored, that’s how the artist meant it to look.

I never take short cuts, never compromise the integrity of a work of art, and never put profits over quality. The proof, of course, is in the results. As a business owner, I don’t have to rush anything. I have the final say, and I insist on the highest standards and proven modern techniques, including acid-free materials, reversible methods, and so forth.

(Read more of the valuable lessons Kate has learned about Working with Art Professionals here.)

You also teach oil painting. Are these careers complimentary?

Kate Wood: I love teaching about art. For twenty-five years (1999-2024), I taught painting at Alizarin Crimson Gallery in Stuart, FL. Recently, I’ve lectured on art restoration for various community organizations, and I have plans to do more of that.

I keep my restoration skills sharp by teaching them to others. Now, I have students who say, “I’m not going to be alive in a hundred years. I don’t care,” but believe me, in a hundred years your great-grandchildren will care. Your restorer will care. Either someone cares for the health of that painting, or it goes in the trash. And the paintings that survive? They increase in value.

Color mixing is probably the most difficult part of oil painting, but because I use that skill almost daily for teaching and painting, whenever I need to match a color for restoration purposes, I am a quick study. Color mastery is rare. Creating natural color is difficult and when you look at amateurish work, you know it by the harshness of the color. If the color’s not natural then your eyes won’t believe it. Now, if you look at the color codes on the back of every paint tube they are all different. One manufacturer’s sap green is different from another manufacturer’s sap green.

So, where do you learn to mix color? Is this a rose, or is that a rose? Whose colors are true to nature? Whose are the longest lasting? I always tell students to seek out the simplest, most substantial, most natural, and most permanent color they can find. Why buy someone else’s mixed color? Payne’s gray? You can make Payne’s gray. Mr. Payne’s gray is just black mixed with ultramarine blue and a little white. Honestly, I’d rather mix those simple pigments than default to Mr. Payne’s gray.

How do you deal with the wide range of materials used in art?

Kate Wood: There’s a huge difference across the centuries. Modern techniques do offer an easily removable minimally invasive process. If you line a brittle painting with Beva, for instance, you can use a relatively low heat to seal and stabilize it. It can also be reversed at a low heat. Unfortunately, some of the wax linings do require high heat. Oil paintings can usually withstand it, but why risk putting one through so much pressure and temperature? Sometimes an old lining is easily removed using chemicals instead of heat.

Where I think it’s important to use the older lining techniques, as far as wax linings, is when the paintings themselves are organic. For example, if the painting uses old organic pigments, or the canvas is extremely old, then beeswax is perfect. New paintings can be difficult to work with. I would rather deal with an old painting because classic painters followed rules and knew something about paint chemistry. Modern paintings are a nightmare: artists paint on bedsheets with no gesso and it’s strung over the edge of some found lumber. Even as an experimenting young painter, I still stretched canvas over stretcher bars and painted a gesso primer on it.

Not long ago, I worked on a 1970s painting on Masonite. All the corners of the painting had been worn away. Masonite is layered, so flaking occurred. What do you do? You have to remake the substructure, but you are trying to keep the art on the face, so it means building it up from the back and finding a level to the original substructure and rebuilding the painting, and the surface texture.

What unique skill do you have that might surprise people?

Kate Wood: As you might expect, I have a thorough understanding of art history, symbolism, and techniques, as well as the requisite hand skills—painting, drawing, sewing, sculpting, casting, etc., but restoration is not just an art, it’s also a science. A professional restorer also needs a working understanding of both organic and inorganic chemistry. First, you need this understanding to safely use the chemicals. Secondly, if you don’t understand the chemical properties of the art you are restoring, then you can’t properly address its problems in a responsible and reversible way. Well, you can try, but that’s not restoration, it’s destruction. I also have mastered the application of fine painted finishes and gold leaf gilding, such as are commonly seen on museum quality frames. However, I’ve been told that the most unique skill I have is replicating broken ornamental glass. A few times now, I’ve also recreated painted stain glass panels that matched the damaged original.

What is the biggest challenge you face in your work?

Kate Wood: The biggest challenge is getting across to people that damaged art and other old objects can be saved. An experienced and trained conservator can save a work that seems beyond repair and in every case, this is preferable to do-it-yourself restoration, cleaning, etc. This is why I always take before and after pictures, why everything I do is reversible, why I choose the materials and techniques I use, and so forth. People see the old chair with the broken leg and they throw it in the trash. They see the dark painting with the rips in it and they think it’s just been in the attic too long, maybe there are even bugs in it, and so it’s just junk now. Art is thrown away too often, but art can be saved. Through expert restoration, there’s a way to make it shine and have it for future generations.

-

To make an appointment with Alchemy Fine Art Restorers, call (772) 287-0835, or email katewoodartist@comcast.net.